And here’s how it all begins…

It’s early one morning, about fifteen years ago and I’m driving my daughter Matia to school, to her grade three class. I’m sleepy from a late night of work, not making much conversation as Matia’s looking outside her window at the passing landscape. Out of nowhere she slowly turns to me and gently asks, “Baba, what does school have to do with anything?”

Matia’s question takes me by surprise and like a bucket of cold water splashing my face, wakes me up out of my daydreaming head and into the clarity and reality of my daughters enquiry.

I fumbled to quickly make up an answer that would explain and justify what school has to do with anything. I pointed out how her learning about numbers in Math will help her when she grows up to use money and to have her own business, and how learning about other countries in Geography will help her to learn about places she might travel to one day. I accurately pointed out how learning how to read and write would help her write letters to her friends and help her to read her favourite books when she grew up and perhaps even to help her write her very own book one day.

But as I looked at her looking at me, patiently listening to my reasoning, waiting for me to come up with even one answer that would quench her curiosity, she slowly turned away and looked out again at the landscape passing outside the car window. And as I looked at her staring out the window, I knew that she hadn’t believed a single word that I had said.

We arrived at the school parking lot, hugged good bye, and then Matia disappeared through the front doors of her elementary school and into another day of sitting at her desk in her grade three classroom.

Driving back home, I thought about Matia’s thoughtful question: “What does school have to do with anything?”

I wondered if she was asking, “What is the connection between school and my life, between learning and me?” In plain words, “Why does school matter?” I thought about the answers that I had given her and realized that I didn’t believe me either. I realized that all my explanations and justifications took place in some distant future, that I was asking her to trust me that one day this would all make sense, just not right now. I was asking her to believe that one day when she was all grown up, she would find all the things she was studying in school, all this magic information that I could see but she couldn’t, amazingly useful for existing in this world. It never occurred to me to look at it from her perspective, as a young girl experiencing the world in the present moment and wondering what the heck all this learning had to do with her life and with anything at all. How frustrating that must be for her. I felt a shiver inside me and felt like I wanted to cry. School was failing her and now I felt I was failing her too.

But why didn’t school matter to my daughter? How is it that she did not see the connection between what she was learning and what she was living. Even though I believe that school matters, if Matia didn’t see how it matters, then it didn’t matter at all.

Matia’s enquiry rekindled in me some kind of personal frustration, perhaps even a kind of anger, about school that must have laid buried inside me for several decades.

Her question got me thinking about my own experience in classrooms, sitting in desks but looking out windows. Apart from a few exceptional teachers who actively sought out how to help me see what school had to do with my life, for the most part, I too had asked that very same question. I just never realized that I had and unlike my daughter, I never had the courage to ask it out loud.

I was a disconnected and distracted high school student, barely passing my way through grade 10, 11 and 12, and though I had a great time learning as a teenager, it was almost always due to my interests and explorations outside of the classroom as opposed to any explorations within it.

I played drums since grade 8, was passionate about music, and in grade 12 learned how to put together a band, book a recording studio, commission artwork, produce a vinyl record that made it to the radio, learn some basic skills about bookkeeping and selling records and all the things needed to have a little amateur rock and roll band.

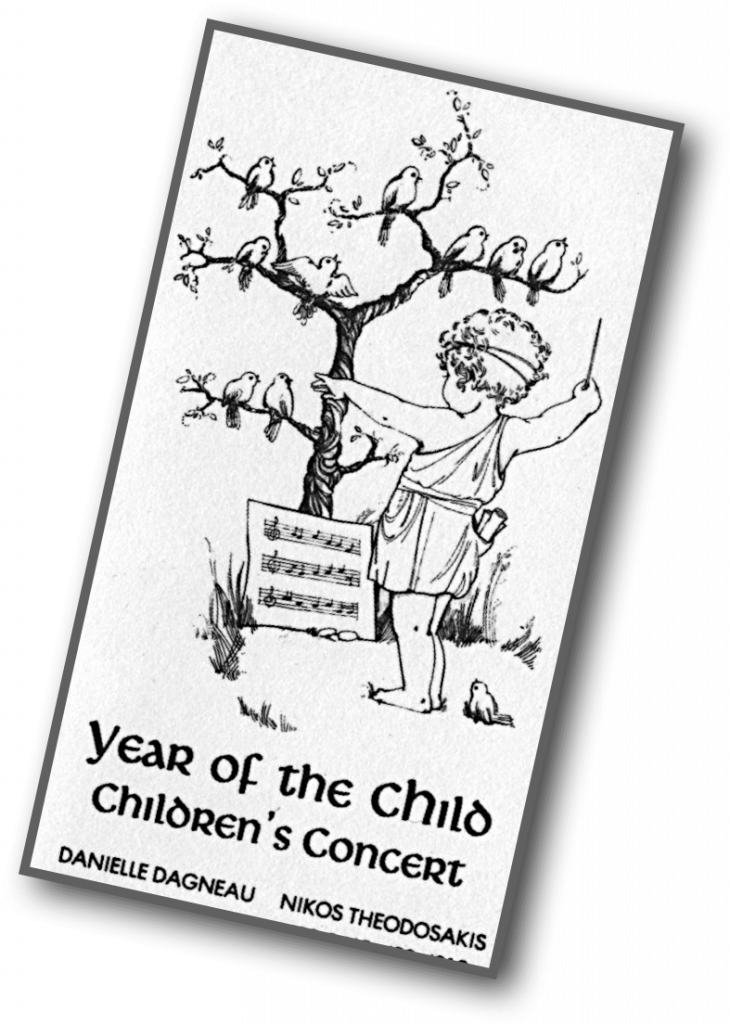

In grade 11 I produced a concert in my community for the Year of the Child, a United Nations initiative to celebrate children, so I learned about booking venues, raising sponsorship, writing letters, booking acts, marketing, and the technology and people involved in running a live show. I was just getting interested in film and photography so I was learning about cameras, darkrooms, the physics of light and sound, and the magic of the filmmaking process from idea to screen. In grade 11 I was the vice president, and in grade 12, the president of my high school, and was joyfully engaged in high school politics and leading the discussions and actions on making the school year enjoyable and meaningful for my fellow classmates.

On the weekends and often during the week, I was working at Theo’s, my parents Greek restaurant, mainly in the kitchen, preparing salads and appetizers, learning about the creation of food, the service of dinning, and the many details and responsibilities that sustain a vibrant family business. Life was so exciting, school – not so much. If anything, school seemed to be something that stood in the way of my real life.

One day the principal called me into his office and spread out manila folders on the table full of my history of academic test scores and achievements. He reminded me that I had been in a gifted program in my earlier school years, and expressed how disappointed he and the other teachers were in my lacklustre performance in high school and that I should pull up my socks. Apparently I had the potential to be a “great” student, but showed no real interest in learning. I remember sitting there, listening to his warnings and thinking, “I am interested in learning, but what does school have to do with my life?”

In retrospect, I suppose it all came back to this question of relevance; I failed to see the purpose of what the subjects I was learning inside of school had to do with my life as a busy, engaged, creative, curious person outside of school. In that chapter of my education, my life in school and my life in the world were out of alignment. In all honesty, school did not matter for me either.

So Matia’s question that morning brought up again this unsettling feeling in my gut that something was still missing and unresolved in our classrooms. A feeling that there was still a large and exhausting gap between what students want to learn, what teachers are asked to teach, and a way to weave the two together.

I wondered if in twenty years my grandchildren would be asking Matia as she drives them to school, “What does school have to do with anything?” and I shuddered to think that nothing would ever change.

Sometimes journeys begin with a single question. Matia’s launched mine.

I began paying closer attention to my daughters learning and found myself wanting to be involved in some way. At the same time, I was participating more in the school tours that my mother was occasionally giving around our restaurant to elementary students. I enjoyed seeing the students reactions to being there, asking questions, excited, stimulated by the wide palette of sensations, and connecting what they were learning in school, especially in their grade seven Ancient Greek studies, to real life.

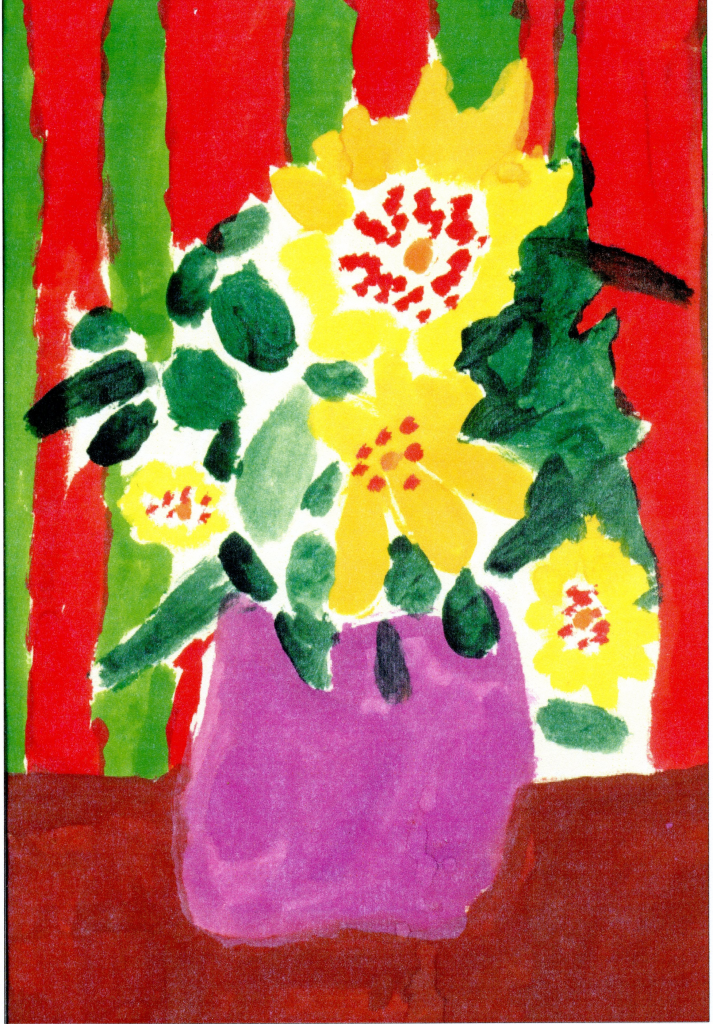

One morning I was walking down Matia’s school hallway and was struck by the beauty of the grade three students large vibrant paintings of sunflowers and I invited the teacher to put them up on display in our restaurant. Unknowingly, this very soft act was the beginning of my ongoing interest in connecting what happens inside a classroom to the world outside that classroom.

Later on, at Matia’s invitation, I started working with my daughter and her friends on a grade four video project, and that led to my awareness of the power of filmmaking in the classroom for developing real world skills of collaboration, communication, problem solving and much more. With my background in producing and directing films, I could see how the process that filmmakers use in taking an idea from concept to presentation could be transferred into a classroom setting, and by doing so, provide structure, instruction and support for these young filmmakers to successfully see their ideas come to life on the screen. I could also see how students passion for creating with video inspired their excitement for research and playful studies and that the act of creating something real, like a film, was an opportunity to do something that mattered.

This led to me sharing my thoughts with other teachers in my community who were also interested in using video in the classroom but felt overwhelmed at the technology and the mysterious process that shrouds the making of a movie. I soon became very interested in the potential of film in the classroom, researching what was happening around the world, trying things out with local teachers, and with those experiences and gained knowledge began presenting professional development workshops for educators in my community and then in communities around my province.

Around the same time, my friend Ian Jukes, an educator and futurist who had walked into my restaurant and my life a few years before, was very excited at what I was doing with filmmaking in the classroom and encouraged me to write a book and share with teachers what I was doing in my workshops and with my school projects. He arranged for me to speak at at the Computer Using Educators conference in California where I presented my thoughts and experiences on using film production in the classroom and the potential that I believed it held. I wrote the book The Director in the Classroom: How Filmmaking Inspires Learning and it found it’s way into thousands of classrooms and became part of many university teacher training programs in North America and then around the world.

As I found myself presenting at education conferences and working with school districts throughout North America, I tried to balance explorations and suggestions of “how” we make films in the classroom with “why” we make those films. As well as advocating the potential for integrating skill development within curriculum and content exploration, I have also championed for projects that help students connect to community, to family and to them selves. Well designed filmmaking projects hold the potential of helping students explore and expand personal connections, interests and passions. In this way, filmmaking projects can matter to students, and hopefully, demonstrate how learning and how school matters too.

This interest in how filmmaking can help make learning matter must have been the seed for a broader question, and a broader examination of school, which wanted to explore how the entire process of learning mattered across all subjects, not just through filmmaking.

That led me to begin a project called InStill Life, which invites elementary school students to lend money to small scale farmers in developing countries around the world. Through a wide spectrum of subject areas, including geography, math, science, language arts, technology and art, students discover the interconnectedness of curriculum and the interconnectedness of themselves with others around the planet. After some playful examination of food and art, the students create a painting, which becomes a greeting card, which is then sold throughout the community. Those funds are then lent out as zero interest loans and through the school year are repaid by the farmers so that the following year’s students can lend them out again. In this project, students apply what they are learning in different subject areas towards a real life project, one which benefits real people and their families around the globe.

The success of the pilot project encouraged me to continue and to expand it to more schools and to build partnerships with likeminded organizations to grow it further. As we listened to the informal feedback and the formal interviews with students, teachers, principals and parents, the conversations inevitably supported the same finding – that because of the realism and relevance inherit in the project, the students found connection, meaning and purpose in their learning. The students felt the project was important because it was about something real, and they were doing something which actually helped and changed the world.

Suddenly, school mattered.

When speaking at conferences, I began sharing my experiences with InStill Life and other projects which I believed demonstrated this philosophy of mattering. I was hoping my observations on these projects could help offer a departure point to conversations about creating more engaging and vibrant project design, where students could see what school had to do with anything. In speaking with educators following these presentations, I saw that there was a great interest, I would say perhaps even a hunger, to move teaching and learning strategies towards a more “mattering” design. But there was also much apprehension about how in fact to do so. Given the immense challenges and restrictions already present in a teachers structured teaching day and the overwhelm of things to cover before the end of the year, the disparity of how and what students wanted to learn with how and what teachers were asked to teach, remained.

I began offering Mattering workshops for educators, where we would look at the purpose, ingredients, design and desired outcomes of a Mattering project and then explore within those small group settings how each participant could integrate more relevance into their current or future projects. I felt it important to reassure that any movement in this direction was to be celebrated. Some participants immediately saw ways to integrate real life student, family, community or global issues into the design of their real world projects and purposeful outcomes. For others, success was in looking at a worksheet and reframing the questions to be a little more personal, a little more relevant to that student’s real life. Others were quick to explore collaborations with other educators in the workshop and to look at how they could partner on projects, each taking manageable responsibilities and together offering students something engaging and exciting. And in that design, also creating something engaging and exciting for themselves as teachers. Regardless of the leap of change that was imagined, somewhere, movement was possible and somewhere movement happened. The last slide in my Mattering workshop says “Start where you can!”, a reminder that this is a continuing process, an ongoing exploration, and a journey that begins by beginning.

After many presentations, workshops and ongoing invigorating conversations with educators around the world, I continue to hear a passionate plea for consideration in how and why we learn. I feel the excitement, curiosity and determination to move the learning experience of students and the teaching experience of educators towards instructional design that incorporates real world relevance, purpose and meaning for all.

In my opinion, the purpose of education should be to help awaken the greatness and the potential that lies inside each child, and that much of the success of that awakening rests in the degree to which we can help students see the excitement, magic and relevance of learning. I believe that we can indeed design learning environments and experiences that help students explore their connections to family, community and self and by doing so, enables them to see what learning and school has to do with real life and specifically their own real lives. I believe that all educators, parents and all citizens of a community have the ability to contribute to creating a change that moves teaching and learning towards a rich learning experience that matters.

I wrote this book because I wanted to share some stories of projects that I think matter. Some quite small, simple and taking place in a few hours, and some much more elaborate, challenging and encompassing an entire school year. I don’t pretend to offer an exhaustive catalogue of relevance based project based learning examples, I am simply offering a story of a journey so far, my journey, and in the telling of that story, hope to inspire others to begin their own journeys into this world of mattering. My wish is that readers discover seeds of inspiration and germinate them into their own projects and into their own personal stories and in the process, create learning that matters.

Thank you for being on this journey, I applaud your curiosity. Start where you can.

Nikos Theodosakis

Naramata, B.C 2020