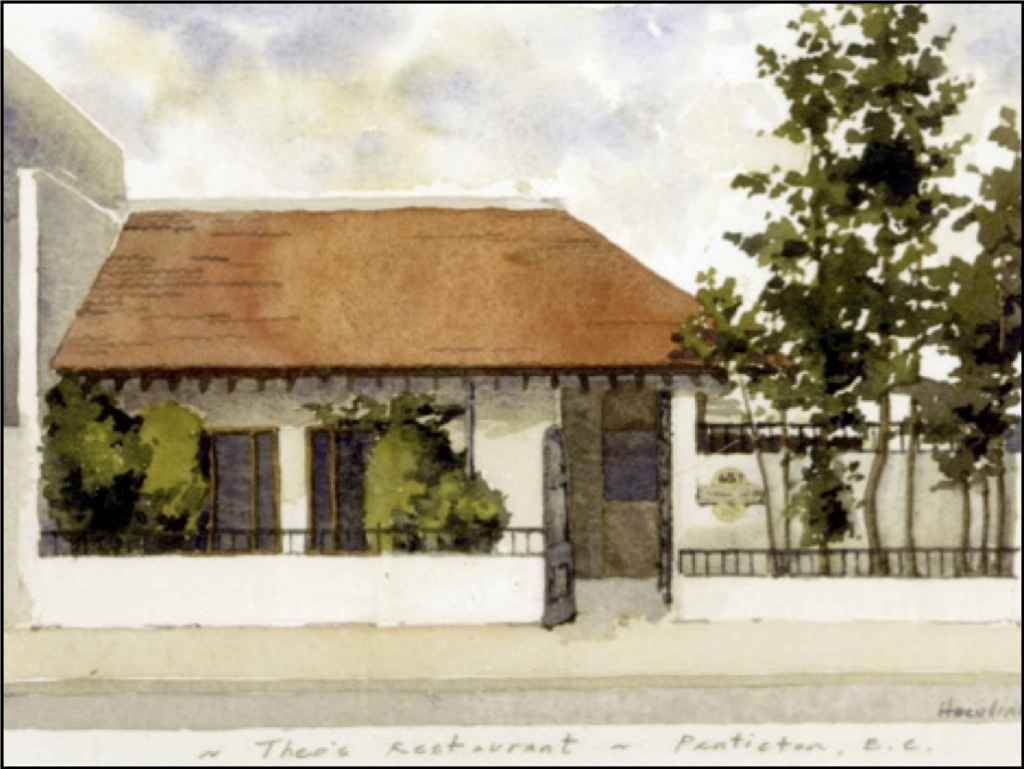

I first discovered that my family’s Greek restaurant was also a classroom shortly after my parent’s Mary and Theo opened Theo’s Restaurant over forty years ago, in 1976. In the mid 1970’s, in our small agricultural town of Penticton in the interior of British Columbia, most people had never eaten squid, or octopus, lamb, rabbit, sweetbreads, moussaka, baklava, stuffed grape leaves or spinach pies. Just those lucky few who had been to Greece may have had a chance to try the distinct, sharp resin flavour of the white wine know as Retsina or experienced the sweet licorice smell of ouzo. All these foods and flavours, naturally familiar to my parents from their native Crete, and part of my own sensory vocabulary growing up, were understandably foreign to most people in our little town.

The building itself was also unique. Unlike the dark wood panel walled and purple shag carpeted steak houses of that era, our restaurant looked like a Mediterranean home, albeit a large one, sitting out of place in our city’s downtown. Sprawling over three floors, it was a labyrinth of rooms, each with its own characteristics and flavour and all drawing from a natural palate of wood, stone, tile and stucco. It held three hundred people and over the four decades that my family operated it, it accumulated artifacts and stories which took up residence on every wall and in every corner of the building.

As a teenager working as a waiter in our dinning room, I found myself as a kind of cultural ambassador to our guests, explaining not only what the menu items were but the history around them. I enjoyed the telling of stories that brought to life and illuminated my Greek culture that perhaps was faintly known by those at the table, but one in which I had experienced through my visits to Crete, and my growing up in that magic circle of Greek culture at home. I recognized from an early age that our restaurant was more than a place that sold food and drink. It was also a place for learning.

From the bouzouki music that greeted guests walking through our front door, to the antique Greek tapestries hanging on the walls, to the old hand painted pots on the mantle, to the Greek dancing and smashing of plates; a night at Theo’s was more than dinning, it held the potential to be an expanding experience for those who were curious. And when questions of Greek culture were asked, I found myself only too happy to reply. I was 16, I was a waiter taking orders and serving food, but I was also explaining the language, the music, the knick-knacks on the wall, the history of the objects throughout the restaurant – in short, I found myself organically emerging into and enjoying the position of tour guide, interpreter and story teller.

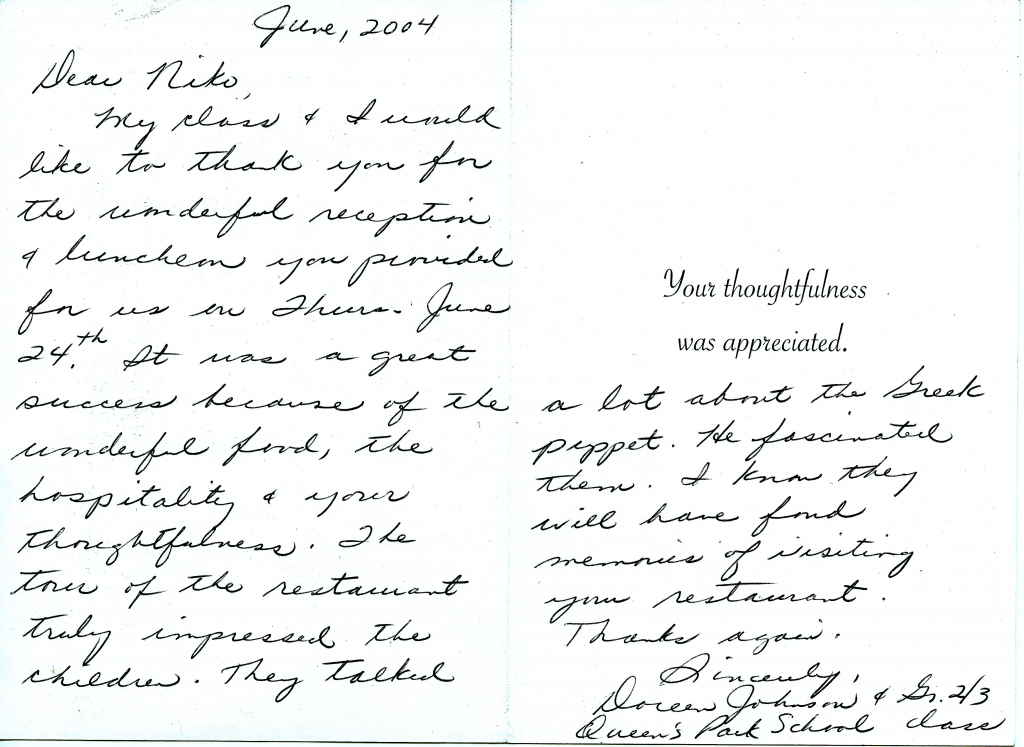

Perhaps it was in these personal table-side experiences where I first saw how questions, stories, and learning intertwine and have the potential to provide an unending stream of discoveries, discoveries which enrich deeply the present moment that we are experiencing and sharing. I saw our restaurant transform into a classroom every time I watched my mother give tours to the teachers and students of our community. Teachers would bring in their students, usually elementary grades, and my mother would enthusiastically and lovingly lead them through the restaurant, pointing out the artefacts, design and beauty of each room and then she would inevitably end up in the kitchen. There she would hold up a large octopus or calamari and have the kids pass them around, delighting as they grimaced, squirmed and giggled at these exotic slimy sea creatures.

Then the students would all wash their hands, head over to a large table in the dinning room, and sit down to a lunch of Greek foods that usually included Kalamata olives, feta cheese, Greek salad, spinach pies, stuffed grape leaves and of course the famous calamari that they had examined earlier. She would point out the connection between all these foods on the tables in front of them that they were about to eat, and how the ancient Greeks would have eaten many of the exact same things in their own lunches. In fact the olives on the table might have been harvested from the same tree that provided olives to Greeks 3000 years ago. Kids thought this was cool. I still think it is.

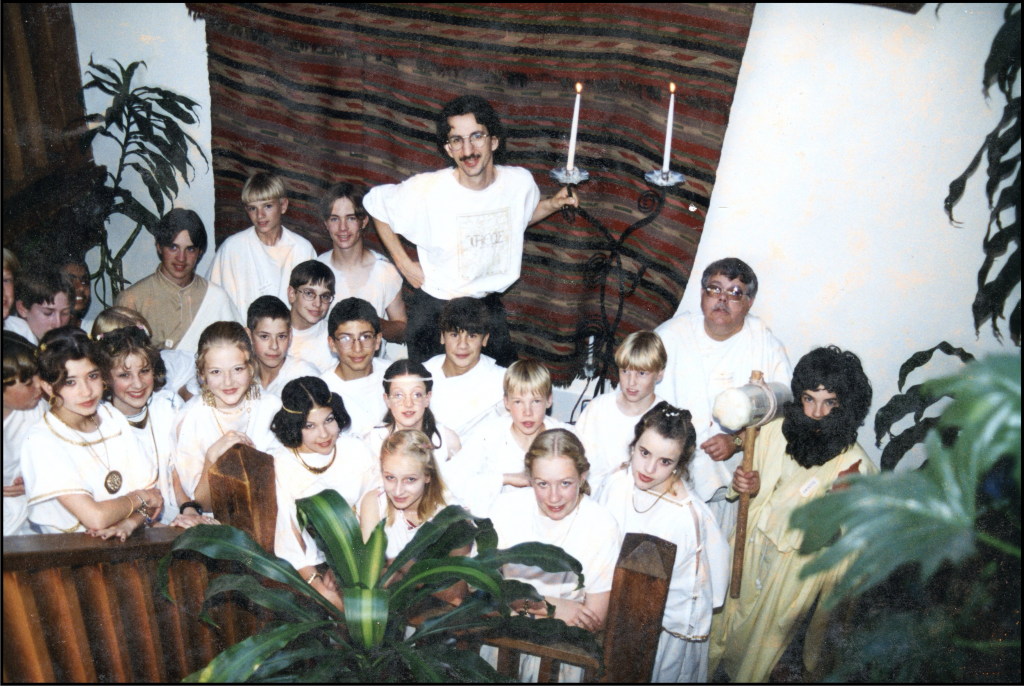

As I got older, I also helped present these tours. I would greet the group of students at the door and invite them inside, briefly explaining the history of our restaurant before beginning our walk around the different rooms. Often these groups would be Grade 7 students, sometimes dressed in bed-sheet togas, who were studying Ancient Greece as part of their grade seven social studies curriculum. As we walked through our three hundred seat restaurant, with it’s beautiful architecture of rough massive wooden posts and beams, it’s flagstone, wood and ceramic tile floors, rough white stucco walls and sun lit courtyards, I would often point out to students how the design of our restaurant had it’s design origins in the palaces of King Minos on the island of Crete, almost four thousand years ago.

The ancient civilization of the Minoans also used wooden posts and beams, stone and plaster covered walls, and designed their buildings in the same way to ward off the hot Mediterranean sun, with tall rooms for the heat to rise away from the people and white walls to reduce the heat absorption. Since we live in the Okanagan Valley, an area of Canada famous for it’s scorching hot summers, this same building design made sense thousands of years later. As we continued around our walk there would be an ongoing conversation, with questions and answers, about the similarities and differences of the Ancient Minoan civilization and our own. The Minoans, for example, were not sustainable users of timbers, and most of the island of Crete lost its heavily wooded oak and pine forests in the pursuit of building palaces and the ships used in trade and in defending the island. We live in British Columbia, where forestry is one of our main natural resources, so I could ask the students “What can we learn from the mistakes of the Minoans?” “What is the connection between people cutting down trees in that ancient civilization and people cutting down trees in our own province?” And the fact that there was a connection, that there was a thread that conected us today to those people of the past was a remarkable opportunity to investigate history through a modern lens.

The palace of Minos had decorative painted frescos on its walls. We had photographs, water-colours and tapestries. On one wall, a hundred year old faded oil painting, referencing a Greek myth, depicts a young boy and girl on the back of a flying ram. The painting provided an opportunity to discuss Greek myths, and in particular to ask if the students knew which myth was being depicted. In this case, the myth of Phrixos and Helle, the brother and sister who were rescued from near sacrifice and were returned home on the back of a flying golden ram named Khrysomallos, the ram whose golden fleece became the treasure sought in the quest of Jason and his Argonauts, a more familiar hero to the younger crowd. It’s a painting that you could overlook as you walked by, and it could also be a painting that would draw a group of students in, and take us collectively back deep into a shared culture where myth and history overlap and were heroes and heroines once ruled.

On a wall in the courtyard, a series of water color paintings capture moments from everyday life in modern Greece. A grouping of fishermen mending their nets by their boats prompts discussion about fishermen, fishing and the kinds of seafood they might catch, including squid! Letting the kids know that Greece has over 1,000 islands helps make sense why seafood is such a big part of the Greek diet since ancient times. I remember asking students about their own connection to fishing, and many did have experiences fishing, as we live in an area rich with many lakes.

A water color painting of a man baking bread reminded me of when I was younger and my aunt Marika would bake bread in her outdoor oven in my dad’s village of Makri Toixos, near Chania, and the fantastic taste of the fresh hot thick bread she would give me to dip into a bowl of green olive oil. So I would recount this delicious story and invite a conversation about baking and eating and what kinds of food everyone loved to eat and their own food making and eating memories. And then we would walk a little further along the restaurant and look at the many black and white photographs of my family in Greece. My uncle Lefteri in his studio, hand carving musical instruments from pieces of wood, having learned the trade from his father, who learned it from a Turk who sold him a little shop by the harbour in Chania in the early 1920’s. On the walls of his studio, you could see all these intricate tools and beautiful instruments. So we would talk about musical instruments and music, and students would share their own experiences with music, sharing stories of agonizing piano and violin lessons, endless practicing and nervous recitals.

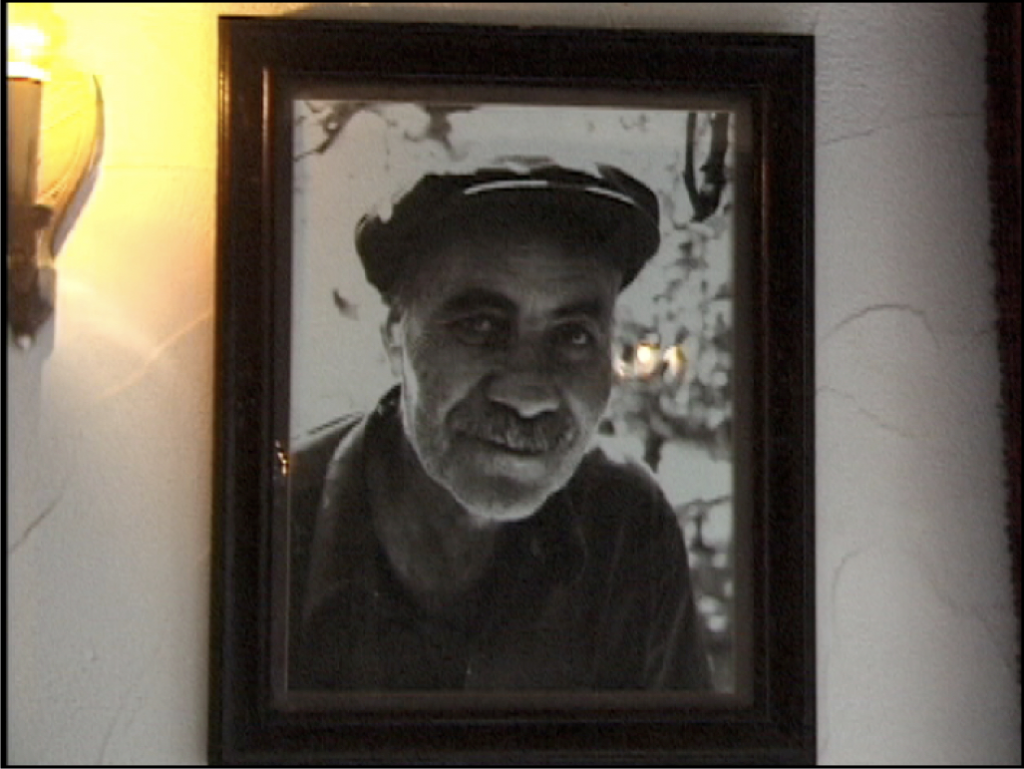

And then there was a black and white photo of my uncle Kosta. When I was 19 and visiting in Crete, I was helping him irrigate our family’s orange trees one afternoon, and he paused for a moment, and I captured his smirk in his photograph. This portrait hangin on the wall would lead to talking about orange trees, farming, and the kinds of trees growing in the Mediterranean compared to the fruit trees that grow in our own Okanagan Valley.

From one of the mantles above the dinning room, I would reach up and take down vintage cameras from the 1940’s, 30’s and 20’s for students to look through and pass around. I would gingerly share a glass negative for them to hold up to the light and see a portrait come to life from the past. This would lead to conversations about cameras and film and negatives and printing and ultimately about how technology has changed. And of course, it was also a chance to talk about their own connection with cameras and photography.

A photograph of my grandfather standing in his military uniform in the 1920s, with gun and bands of bullets across his chest, prompts questions from one of the students in a toga. “Why is he dressed up like that?” and “Which war was he fighting in?” I’m explaining where our family was during the First and Second World Wars and who was fighting where. Suddenly, we are exploring world history and that investigation was sparked by a portrait of my grandfather which happened to catch the eye of one of the students.

Eventually the tour would be over and we would sit down at long tables in the dinning room, bring out the Greek food and begin to eat. With each different plate of food, there would be a story or a connection, like those three thousand year old olives that my mother would talk about. There would be the pungent Feta cheese, or the Kefalograviera cheese made from sheep milk, and the bowls of extra virgin olive oil to dip fresh hot bread into. We would serve Yigantes, which are giant white beans baked with honey and red wine vinegar, and another example of a dish that ancient Greeks ate thousands of years ago and which they are still eating today. I explained to the students that they did not have tomatoes in ancient Greece or Rome, so they used honey as a sweetener and the vinegar to balance the taste. So it was a lunch with a menu that reached far into the past, and in a way challenged the students to try something new and to see how our ancestors ate, many many years ago. After lunch, the school bus would arrive, and transport the students out of Greece and return them to a 21stcentury classroom in the modern day city of Penticton.

My mother and I hosted dozens of these restaurant tours these last four decades, and despite the different age groups and interests, one thing was constant. When we walked around Theo’s, each experience was different. Each student affected the tour by their own interests and by extension, their own questions. Although the tour may have followed the same physical path around the building, the path of questions and stories changed and evolved. Each unique school tour reflected those students collective connections and observations about their own life as reflected by and prompted by the objects they interacted with. Every antique, camera, tapestry, piece of furniture, type of food, music, and artwork was a potential door-way which could lead to further questions, stories and explorations.

When I answered questions using real-life experiences, wether my own or of the people I knew, I felt I was offering students authentic connections that helped make the theoretical real. I believe that by offering them an authentic context for these connections to happen within, I was in fact helping them see the connection between what they were learning in a classroom and what that learning had to do with real life. That in fact, learning about ancient Greece might actually have something to do with their own lives today. With these real life field trips, abstract concepts became tangible and school stopped being about a pretend world and began being part of a world of real flesh and blood.

Mike Palmer, a teacher who brought in 42 grade seven students from Trout Creek Elementary many years ago, all who were in togas, including himself as Socrates said this, “In the classroom, we lay the foundation for learning, but the kids need to go out into the community to make the connections from textbook to real life.” What a wonderful discovery and privilege to realize that our little Greek restaurant could be a bridge for connection and for making learning real. I can recall many instances during these tours when I witnessed students have an “A-ha!” moment as something clicked for them and they saw the truth between an abstract concept and their own life.

And in these tours were my own “A-ha!” moments as well. These school tour experiences enabled me to see that when students are able to place information and what they are learning within the context of real life, especially within their real life, then “aha!” moments happen. I saw these “a-ha moments” happen in front of me, that instant when students realize that what they are learning about at school has something to do with real life and their own real lives, and that it matters.